Nosferatu: Murnau, Herzog, Eggers

Revisiting the Symphonies of Terror

I will be mercilessly “spoiling” in the following “vampirological” film review, otherwise it would bore me a bit to write it. I have long been looking forward to Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu, the second remake of the classic German silent film by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. I wasn’t disappointed (I don’t expect much from movies these days), but I wasn’t exactly happy with it either.

To explain why, and to understand what Eggers did with the source material, I have to go back a little.

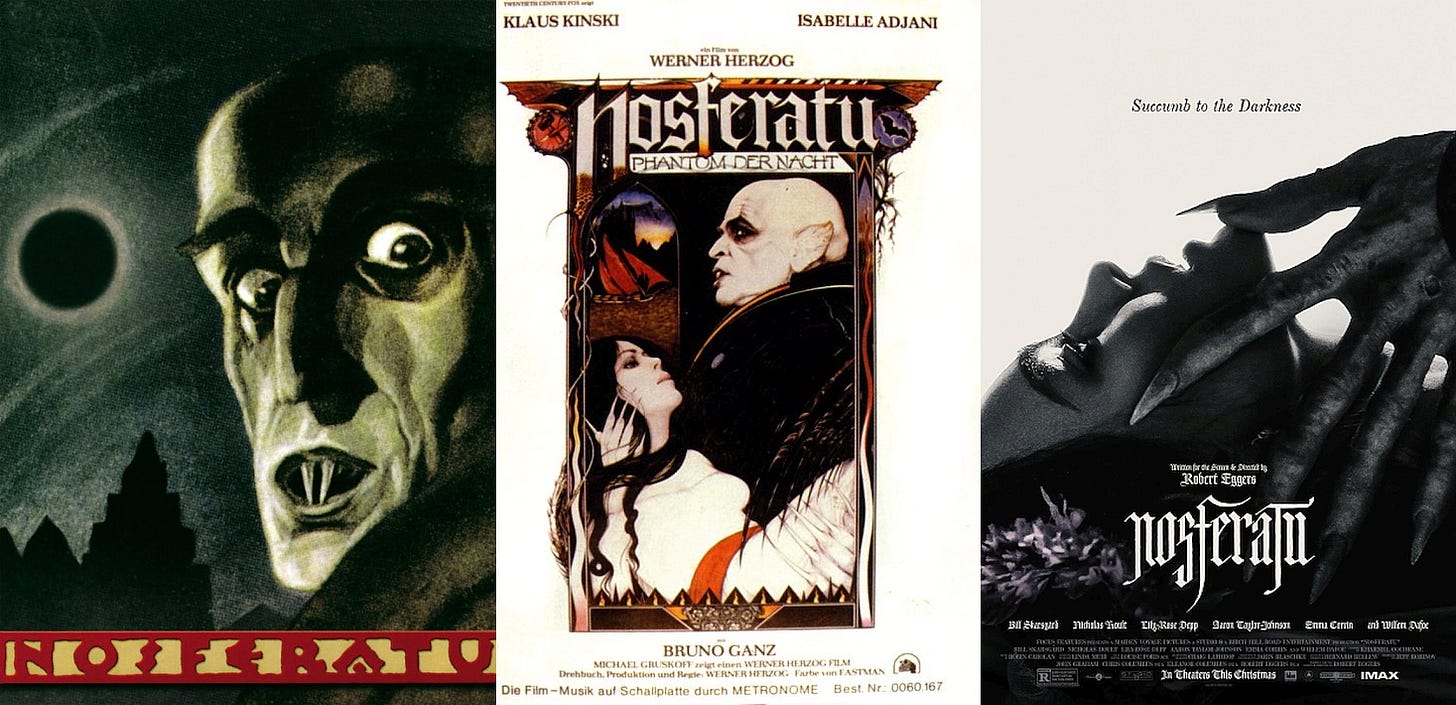

The groundbreaking original from 1922 is one of my all-time favorite films. I saw this “Symphony of Terror” for the first time in the fall of 1989, late at night on Austrian television, as part of the legendary Kunst-Stücke (“Art Pieces”) program, hosted by square-head Dieter Moor, who today inexplicably calls himself “Max” Moor. I still have my original VHS recording of the broadcast. (It was preceded by three episodes of Louis Feuillades 1915/16 serial Les Vampires.)

The version shown was the 1980s restoration by Enno Patalas, with a newly composed, fantastic score by Hans Posegga which I prefer to Hans Erdmann’s original. Unfortunately, this version has not yet been released on DVD (to my knowledge).

Since then, I must have seen the movie about forty times, including several times at the cinema with live musical accompaniment. There are several versions on YouTube; a good-quality one with English subtitles can be found here, for example.

So much has been written about this enormously influential film that I can spare myself the big words here. Nosferatu – A Symphony of Terror is the original godmother of all vampire films, if not (together with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Golem: How He Came into the World from 1920) the horror genre itself.

There is hardly a vampire film that has not drawn on it in some way, whether directly or through conscious and unconscious iconographic genealogies. At the same time, Nosferatu is one of very few silent films still popular and accessible to a wider audience today, more than a hundred years later.

F. W. Murnau (1888-1931) is considered one of the pioneering giants of early cinema. He left behind many important and influential works, including The Last Laugh, Faust, Sunrise and Tabu. Murnau, his scriptwriter Henrik Galeen, who specialized in fantasy, and the enigmatic producer Albin Grau, who was also mainly responsible for the visual design, reset Bram Stoker’s Victorian novel Dracula (1897) to a Biedermeier Germany in the vein of E. T. A. Hoffmann, in a fictitious town called Wisborg, located by the sea. To create this town for the film, a mixture of original locations in Wismar and Lübeck was used.

Galeen’s script reduced the novel’s ensemble of characters to three main figures, to whom he gave new names: Dracula/Orlok, Jonathan Harker/Hutter and his fiancée Mina/Ellen. Renfield, the mad insectivore, fanatically devoted to his undead “master”, reappears as the real-estate agent Knock. The role of Van Helsing is at least faintly echoed in the character of Dr. Bulwer (named after the novelist Bulwer-Lytton), a “Paracelsian”, who however is not a vampire hunter.

After Orlok arrives in Wisborg on an empty ship steered by his ghostly hands and whose entire crew he has killed one by one, the plot deviates greatly from the original: from coffins filled with cursed soil “from the fields of the black death” the vampire brought with him, masses of rats emerge and cause a plague in the city.

When Hutter’s bride, Ellen, reads in a book her fiancé brought from Transylvania titled “On Vampires, Horrific Ghosts, Sorcery, and the Seven Deadly Sins” that the spell can only be broken by a “sinless woman” surrendering to the vampire and making him forget the first cock crow, she decides to sacrifice herself to end the mass death.

Galeen’s adaptation is simply ingenious. From the novel’s somewhat convoluted plot, he distilled an eery romantic fairy tale in which the female protagonist, no longer a mere passive victim, becomes a heroine through the power of her love.

He created a “Germanized” alternative Dracula, which has since led a legitimate “life” of its own alongside the Anglo-Saxon original, which was not filmed until 1930 with Bela Lugosi in the leading role under its original title (albeit based on a then-popular stage play, not the novel itself).

Murnau/Galeen/Grau also created a vampire archetype that has survived in popular culture to this day: haggard, balding, with pointed ears, rat-like front teeth instead of canines, spider-like hands with long claws and a posture and moving patterns as if rigor mortis has already set in - that’s “Nosferatu”, not “Dracula”.

He was played by an enigmatic actor fittingly named Max Schreck (=“Terror” in German), who is remembered today only for this role. Thanks to him, Nosferatu is the only movie which makes me believe I am watching an actual vampire every time I see it (an idea that was taken up in 2000 for the rather disappointing movie Shadow of the Vampire).

Countless viewers of the film have had this strange impression of “authenticity”, paradoxically all the more if their first encounter was a washed-out copy of the umpteenth generation on television or VHS. Robert Eggers also experienced it as a child.

The “Nosferatu” type, an animalistic relative of rats and bats, with hardly any human traits left, is far removed from the later seductive, suave Draculas like Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee and their countless heirs, or the sexy rock stars in the novels of Anne Rice. He has remained an enduring alternative, and appeared, among other things, in the 1979 Stephen King film adaptation Salem’s Lot (as well as its rotten “diversified” 2024 remake).

In the same year, Werner Herzog remade Nosferatu with Klaus Kinski in the title role, joined by Bruno Ganz (Hutter/Harker) and Isabelle Adjani (Ellen/Mina/Lucy), under the title Nosferatu – Phantom of the Night. This version is based on Murnau’s 1922 film, not on Bram Stoker’s novel (although the main characters have regained their original names).

Herzog more or less copied Murnau’s pictorial compositions and staging, but in color, and with actors who sometimes act in the silent film style and repeat exactly the gestures of their predecessors from 1921. Other scenes he playfully varied and modified.

Thus, Phantom of the Night is more a “re-enactment” than a remake of Symphony of Terror. The idea behind it is maybe that a cinematic work is a composition that can be replayed just like a piece of music can. Gus van Sant tried something even more extreme in 1998 with Hitchcock’s Psycho, but with little success.

Like Murnau, Herzog drew his atmospheric magic from original locations, some of which are the same, such as the High Tatras in Slovakia and the Lübeck salt storehouses, which in the film serve as a species-appropriate dwelling for the vampire. It was not possible to film in Wismar as it was now on GDR territory. Instead, the canals of Delft in the Netherlands served as a backdrop for the fictitious German Biedermeier town.

Herzog’s film, very effectively accompanied by the prelude to Richard Wagner’s Rheingold, Charles Gounod’s St. Cecilia Mass and the sounds of Krautrock band Popol Vuh, also breathes the spirit of German Romanticism. But the director also wanted to draw a conscious connection to traditions of German film that were torn down in 1933, to the forefathers of German cinema like Murnau and Fritz Lang.

Lotte H. Eisner, an author religiously revered by Herzog for her influential books on the “expressionist” cinema of the Weimar Republic such as The Haunted Screen, generously attested to his success in this endeavor: “This is not a remake, this is a rebirth.”

As usual, Klaus Kinski is brilliant under thick layers of makeup, but he is visibly Klaus Kinski and not a mysterious nobody or anonymous figure who could just as easily be a real vampire. He adds a melancholic, deeply sad note to the character; unlike Murnau-Galeen’s Count Orlok, he longs for deliverance from his dreary existence as a restless, hungry shadow.

Of course, Herzog wouldn’t be Herzog if he hadn’t put his own poetic stamp on the material, despite his fidelity to the original film. This shows right from the start in the opening credits, featuring genuine creepy Mexican mummies. Some scenes, not least because of Herzog’s typical oddball supporting characters, border on the unintentionally comical, which makes the film easy prey for an unfriendly audience, as I (woe is me) once experienced at a screening in Berlin.

The most significant deviation from Murnau is the “pessimistic” ending: Count Dracula is destroyed by the rays of the rising sun, held back only by the beautiful, pale maiden who gives him her blood, but his victim Jonathan Harker turns into a Nosferatu-like vampire who apparently can survive in sunlight and rides off in the final scene of the film to spread evil further into the world (similar to the infamous end of Polanski’s Dance of the Vampires).

Herzog’s film is captivating today because of a style that was, and still is, completely opposed to “Hollywood”: long, static shots and a generally decelerated, almost trance-like pace that allows the viewers to “hypnotically” immerse themselves in the cinematic space and time. The landscapes and locations are as they were, at most altered only by lighting.

So, what about Robert Eggers and his recent adaptation of the material? Born in 1983, he has been obsessed with Murnau’s film since childhood and has been working on his version for over a decade.

Since his first short film attempts (such as Hansel and Gretel, 2007), Eggers has focused on the horror genre with a decidedly “Northern European” sensibility. This, and the fact that his films have so far been free of “diversity” and “wokeness”, has made him a favorite of the Anglo-American dissident right. They never tire of praising how “white” his films are (see for example here and here), although he, of course, positions himself ideologically in a completely mainstream-compatible framework.

Even if not all of his films fit 100% into the “horror” category, they are all about dark, demonic forces that lead to destruction, death and madness. Evil always wins. In The Witch (2015), a Puritan family in 17th-century New England is corrupted and destroyed by satanic witches, while in The Lighthouse (2019), two 19th-century lighthouse keepers lose their minds due to isolation, excessive drinking and unseen dark, occult influences.

The Northman (2022) may be a Viking movie, but it is also full of supernatural apparitions, shamanistic delirium and, above all, relentless brutal bloodshed. The world Eggers portrays is indeed one of great visual beauty and mythical fascination, but there is also something nightmarish and absurd about its mind-numbing fixation on revenge, combat and slaughter.

The nihilistic streak of Eggers’ previous films culminates in Nosferatu in an almost unsurpassable way (spoilers ahead). This is one of the reasons why I was unable to really like it, despite its undeniable qualities.

The film is certainly a feast for the eyes: the costumes, the sets, the visuals, all of this succeeds on a spectacular level most of the time.

The plot closely follows the Murnau-Galeen template for the most part, but in many respects returns to Bram Stoker. The title character is particularly well done. This was probably one of the biggest challenges for the director, because vampires have become rather (so to speak) sucked dry figures that are no longer very creepy.

Eggers returns the horror to his count. As in the novel, he sports a massive moustache, as a Wallachian prince of the 15th century might have worn it; and similar to Stoker, he is - in contrast to the clichéd depictions since Lugosi - a repulsive, putrid figure, in fact literally a living corpse with a decomposing body. At the same time, the traits of the “Nosferatu” type are clearly recognizable. Eggers has skilfully varied the character without repeating it.

What he has done with the vampire’s voice is also successful. It sounds rough, deep, metallic, leaden, inhuman. Orlok has to take deep, rattling breaths before speaking, as if it takes him endless effort. He has a strong Slavic accent and at times speaks (as I gathered from Wikipedia, I wouldn’t have figured it out myself) “Dakian”, the language of the ancient Proto-Romanians. Authentically antiquated language is a significant element in all Eggers films.

Similar to Herzog, Eggers also plays intriguingly with elements from Murnau, be it sets, props, certain gestures, pictorial compositions or visual motifs (such as the shadow scurrying across the walls). Those who are familiar with the German predecessors of this American revenant will particularly enjoy Eggers’ passionate devotion to details, quotations and variations.

Where Murnau and Herzog find the uncanny in nature, however, Eggers’ digitally-processed world is thoroughly “artificial”. Its perfection also makes it rather sterile. These are the kinds of movie landscapes and sceneries that in the future will probably be created entirely with AI.

The “demonic” element is strongly emphasized. Albin Grau, a member of the magical order “Fraternitas Saturni” and later acquainted with Aleister Crowley, had the real estate agent Knock, who sold Count Orlok a “beautiful, gloomy house” in Wisborg, read a letter from his client written in a secret language of sigils and occult symbols. Eggers spells out in shocking detail what Murnau and Galeen only hint at: Knock practices black magic to summon his “master” to Germany.

It is significant that his counterpart, a Van Helsing-like character called Albin Eberhart von Franz (Willem Dafoe, who played Max Schreck in Shadow of the Vampire), who has lost his academic reputation because he started to occupy himself with occultism, also resorts to magical weapons and spells instead of crosses, holy water and consecrated hosts to defeat the Nosferatu.

In fact, it doesn’t even occur to Franz to try these genre-typical methods, which the scientifically “enlightened” vampire hunters of the classic films (think of Edward van Sloan and Peter Cushing) routinely used like magic weapons that work at the push of a button. In Robert Eggers’ vampire-infested Germany, there are Christmas trees, but no priests and no churches are to be seen (unlike in archaic, orthodox Romania). A small cross around the neck of Ellen’s friend Anna offers no protection at all.

As always, there is no God and no Christ in Eggers’ world, only demonic, devilish, magical, malevolent forces that triumph unchecked.

In contrast to the later iconography of the genre, Murnau also did not employ crucifixes and hosts (in Herzog’s film, the latter still have a certain banishing power, but their effect is greatly weakened), no priests and no prayers, even when the plague rages in the city.

The woman who sacrifices herself to stop the plague is, however, described as “pure” and “sinless”; her love, which transcends space and time, has already, in one of the film’s most famous scenes, telepathically drawn back the vampire when he was about to give her fiancé the fatal bite. For Murnau-Galeen, “love is stronger than death”, even if the hero’s bride dies in the end.

Eggers sabotages this idea by introducing a demonic possession theme that provides the female lead with a central motivation. But here, too, no exorcist with prayers, holy water and incantations can help, nor is any attempt made to do so.

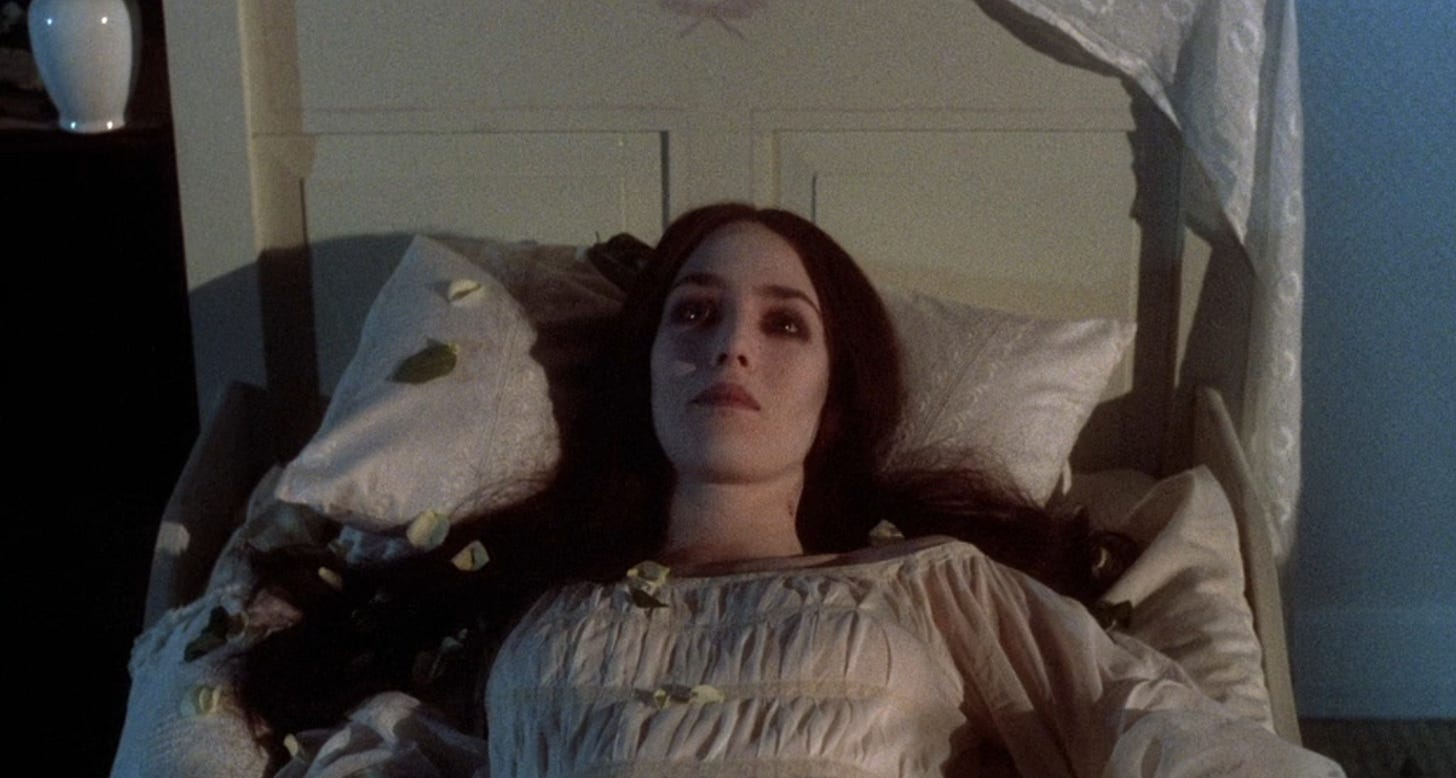

The backstory goes like this: Ellen, who is the central figure in the film even more than in Murnau’s version, called upon a demon during her childhood to rescue her from loneliness and desperation. An evil entity gladly obliged and took possession of her. In the very first scene of the film, we see her, years before the action begins, longingly summoning her “demon lover”, whom she calls “guardian angel”. She writhes in bizarre, supernatural convulsions when he answers her “prayer” and brutally ghost-rapes her.

The movie had barely started and I was already annoyed. The opening sequence was what should have been a climax at the end. Basically, everything was said with this gruesome horror sex attack, and now no more suspense was possible: Ellen belongs to the demon, who turns out to be identical to Nosferatu himself, right from the beginning.

He is basically death itself. Her husband knows about the afflictions that have haunted her since childhood. She tells him, also in the first act, about a dream (you can see the scene in the trailer):

“It was our wedding. When we turned around, everyone was dead. The stench of their bodies was horrible. Standing before me was... death. But I’ve never been so happy.”

When she utters the last, monstrous sentence, her facial features burst into a strange grimace full of perverse, painful, irrepressible joy, while a nervous laugh escapes her. The closer the vampire gets, the more often she loses control of her mind and body, which repeatedly freezes in unnatural, obscene poses, similar to the hysterics described and photographed by Jean-Marie Charcot at the end of the 19th century. Linda Blair’s diabolical contortions in Friedkin’s The Exorcist also appear to have been a model.

Eggers is too sophisticated to turn this into a trite Freudian story about the suppressed sexuality of women in pre-feminist times. Nevertheless, he makes a few half-hearted forays in this direction. The result is rather confusing.

In many scenes, another horror film seems to have been the inspiration: Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession from 1981, a grotesque relationship drama in which Isabelle Adjani (the heroine of Herzog’s Nosferatu) terrorizes her estranged husband with psychotic seizures while cheating on him with a mystic and secretly raising a slimy tentacled monster. In this film, the boundaries between mental disorders, dream visions and demonic influences also disappear.

Particularly, one rather deranged scene seems to have been inspired directly from Possession, in which Ellen draws her husband into an escalating histrionic argument, at the climax of which she provokes him with the words “You could never please me as he could”, causing him to immediately take rough action to prove her wrong. This is one of several instances in which the film descends into crass, self-serving vulgarity.

Vampires and sex, the bite as a substitute or metaphor for coitus – these are certainly not new motifs, but rather old and fixed components of the genre. They are already present in the original film, albeit in an infinitely more subtle way. The sleepwalking Ellen longingly stretches out her arms, reaching for her far-away lover, while Murnau uses a parallel montage to show Hutter and Count Orlok approaching at the same time, the former by land and the latter by sea. Which of the two will become her bridegroom? In the end, it is Orlok, who spends the night sucking her neck until the cock crows and the sun’s rays dissolve him into dust.

Eggers makes this subtext explicit in a drastic, almost pornographic way; in his version, there is biting and shagging. And nothing else. The nature of the relationship between Ellen and Nosferatu is not a grandiose Gothic romance like the one between Gary Oldman and Winona Ryder in the opulent Dracula adaptation by Francis Ford Coppola from 1992 (another all-time favourite), which was advertised under the slogan “Love Never Dies”.

It is rather a pure morbid lust, heightened by fear, violence and abuse, satanic orgasms, similar to those experienced by the young girl seduced by the Devil at the end of The Witch. “I am an appetite, nothing more,” says the vampire, before giving Ellen an ultimatum of two nights within which she must voluntarily declare herself his bride and surrender to him. In the meantime, he carries out a few more cruel acts to blackmail her, such as exterminating the family of her friend Anna (played by an actress who in all seriousness describes herself as “non-binary”).

It is only very late into the movie when the idea arises that only the voluntary sacrifice of a woman can destroy the vampire (and thus end the plague). It is not discovered by Ellen, but by Dr. von Franz in an ancient demonological book.

But since Ellen has longed to be consumed by the vampire anyway, and has actually been obsessed with him since she was a child, her act of sacrifice loses all purity and tragedy and thus also romantic beauty. She sacrifices herself in the end only because she cannot and will not do otherwise, because it is the fulfillment of her most secret, deepest, darkest desires (even worse, in fact she has “solved” a problem she herself has caused.)

Self-sacrifice and self-destructive surrender to death-and-sex lust just don’t go together. The script trips over itself here. In 2024, 102 years after Murnau, it is apparently no longer possible to show a virtuous or “sinless” woman who sacrifices her life out of pure selflessness. It would be perceived as ridiculous, outdated and corny, and probably criticized as reactionary and misogynistic. Isn’t it cowardice on the part of the director to avoid this risk?

The movie ends with a final, bloody death-sex, which comes to an end when daylight finally destroys the undead creature. The last shot shows the naked, dead couple still entwined, Ellen with the (now hopefully really deceased) count’s massive, decomposing corpse between her open legs, bathed in warm sunlight. Redemption, happy end?

Why did we have to watch all of this? Impaled humans and vampires vomiting blood, necrophilic sex acts, doves having their heads bitten off, and, worst of all, screaming toddlers being torn apart by the vampire and thrown away like dolls? (I can’t see any artistic justification for the latter. It is utterly disgusting. Like Hitchcock and Truffaut, I consider killing children in films an “abuse of the cinema”.)

It seems that nowadays horror movies can’t go below this level of crassness, but it doesn’t really shock anyone any more either (I just feel nauseous). It’s amazing what we’ve come to accept as “normal” or at least acceptable in the movies. But did we really need another “Nosferatu” to dish out this kind of fare?

I’ve already mentioned that some right-wingers in the Anglosphere appreciate Robert Eggers as a director who has a penchant for “European” aesthetics and “white” subjects. That may well be. However, they overlook the fact that the worlds he creates are consistently bleak and nightmarish and, as already mentioned, death, madness, destruction and evil always triumph in them (The Northman, which contains some positive elements, may be his least unsettling film). They are works of art from a late, hollowed-out, dying civilization.

However, it is not only the nihilism and bad taste for the morbid and extreme that make Nosferatu a rather unpleasant und unsatisfactory experience.

Even though Eggers is one of the better contemporary directors and one of the last standard-bearers of the “arthouse” tradition, his films are almost as derivative as Tarantino’s are and suffer from the same syndrome as all of today’s cinema: on one hand, there is the compulsion to incessantly bomb the tired and jaded senses of the viewer with stimuli, and on the other creative stagnation, non-stop recycling and re-working of old scripts and images, without producing anything truly new, while at the same time the technical possibilities for realizing the boldest visions are greater and cheaper than ever before.

Nosferatu is yet another stale fruit of the age of remakes, reboots, franchises, sequels and prequels, despite its high aspirations and technical mastery. This revenant will not become a classic, but at best a footnote to the films it has vampirized.

***

An excellent first instalment in your Substack, Lichtmesz. Congratulations!

'toddlers being torn apart by the vampire and thrown away like dolls? (I can’t see any artistic justification for the latter. It is utterly disgusting. Like Hitchcock and Truffaut, I consider killing children in films an “abuse of the cinema”'

Yes this was inexcusable--why?

I'm not sure about Eggers or his films, and by this I don't mean to express moral disapproval--this is beside the point, because to me watching a horror film is in itself an amoral act--but to say that I genuinely don't know what to make of him or them. I am inclined *maybe* to give him the benefit of the doubt more than you are on the Nihilism Question. I tried to say something interesting about this film here:

https://shadeofachilles.substack.com/p/the-better-sl00ts-of-our-nature-in?r=3jr7ai